“Girl, Writer”

”And look. After you make the pages, you bind them together into a proper book.”

How had I not seen it right away? And now that I had seen it, could I go?

Dad usually didn’t see the point of the groups I wanted to join, begrudging the money it cost to sign me up for summer art classes and private violin lessons. I asked Mom about the fees, but she pushed the question aside. She’d cover it, she said. But the program started Friday night. Who would take me? The evening session ran from 5-7 pm, but Mom couldn’t get away from the office before five. Her weeknight routine included rushing home, starting dinner, running laundry, serving meals, washing dishes, and badgering Dad to take out the trash. Though Dad, a schoolteacher, left work at 3 pm, he spent his afternoons at the bar. When it came to driving me thirty minutes across town for an optional extracurricular, he was not available. I told Mom it was okay, that if I couldn’t go, it wasn’t her fault. But I was furious, imagining myself storming down to the TV room and making Dad listen to all the ways he was a bad father, a mean man, a selfish tyrant. Mom brushed my cheek with the backs of her gently curled fingers, her special way of touching me, her way of saying everything between us in one silken instant.

“I’ll make arrangements,” Mom said, promising she would be home in time to drive me.

On the appointed Friday, I walked home from school in a chilly spring rain, splashing through puddles and twirling my umbrella. At home, the raindrops tapped on the wavy glass of my century-old bedroom windows. With the house to myself for hours, I read to pass the time. I was in my favorite place in the world, snuggled in bed with a book, stuffed toys, and soft pillows insulating me, the downy comforter pulled up around my shoulders. With the romantic sound of the rain on the windows under a darkening sky, I imagined I was a princess in a tower, a queen in her castle, an orphan girl rescued from an uncaring world. Bright yellow light fell around the room, emanating from the bedside lamp. Beneath it, I kept a clock radio, a ceramic figurine of two snowy white cats, and a box of tissues for the sad parts of the novels I read until late every night.

”Lights out, Jennie,” Dad had said last night as he passed my door. “Put your book away.” I obeyed, but later, when his thunderous snoring signaled that my parents were dozing, I turned it on again and read until I fell asleep.

The clock radio might have read 2 am before I was done, or even 3 am. When the morning routine started a few hours later, my eyelids were heavy, my movements sluggish, and my mood mulish. Dad snapped the window shades open, leaned over me bellowing, and dragged me out of bed by my foot, bouncing my head on the bed frame and my butt on the floor. Enraged, I jumped up, screaming, fists swinging. When it was all over, I fumed with hatred, and he snorted at my indolence.

”If you wouldn’t stay up reading all night, the mornings would be easier,” Mom said, her tone measured and reasonable.

I protested that I only read books for school, but she knew better. Just one of every four books I read was assigned for class, and she reminded me that no matter how much the teacher praised my choice of hobbies, when it interfered with my sleep, it was too much.

“That’s why your dad loses it.”

”He’s wrong.”

”He won’t change, but you can. Do us a favor, please?”

Today, I read for an hour without stopping, then two, completely unaware of time passing in the real world. If doors opened and closed downstairs, I didn’t hear them. If someone called my name, I blocked it out. On the pages before me, the black type transformed into images and feelings, sounds and smells. I read about everything and everyone, the privileged and the poor. Stories from fairytale lands lived on my bookshelf alongside pioneer girls on the lonesome prairie. My search for new stories was never-ending, but I reread the books I owned like friends who revealed themselves to me in layers. I read my best books so often that they eventually lost their covers, and I struggled to keep their loose pages together.

In the library, I found windows into other worlds, kids who grew up in apartments, kids whose wealthy parents ignored them. When I asked the librarian for a better book about a dog than Old Yeller, she gave me Where the Red Fern Grows. When I needed something new after The Secret Garden and The Little Princess, she suggested The Island of the Blue Dolphins and Jacob Have I Loved. At the annual book sale, she made sure I didn’t overlook Julie of the Wolves. The library had a set of plump reading chairs that nobody used, clustered before a wall of enormous windows looking out to the terraced courtyard, sunny and green. I loved to curl up in them, reading and disappearing into my imagination, sitting up straight when the librarian asked me to take my feet off the upholstery. I forgot so often that she sometimes seemed genuinely angry at me. Startled, I mumbled my apologies, fearing I’d ruined something special. I felt fragile as glass, wondering if she would order me out for always forgetting the rule. Instead, she softened, her eyes seeing something in me that needed this place, these chairs, this room full of paper and glue, and everything it means to be human.

My bedroom door flew open and banged against the wall. Mom’s first words got lost in the blur of coming back to reality, but I gathered we were late. Late for what?

”Your writing workshop,” she said, drawing back the blankets and grabbing my hand. In the bathroom, she dragged a brush through my hair, then led the way downstairs, where she put my coat on me and pushed me out the door.

When we got there, we were the last to arrive. Mom hustled me across the dark, wet parking lot and through the glass doors leading into the community center. There was an acre of grey carpet under fluorescent lights in the lobby, and a lady wearing a skirt and a sweater vest beckoned us to the meeting room. Mom kissed me at the door and promised to return at seven as I struggled out of my coat, and the speaker at the front of the room tried to ignore our disruption. I settled into the back row, all the other kids in rows ahead of me, lined up at long white tables. Each of us had a stack of lined paper and two pencils while a man up at the front referred to a chart diagramming a paragraph. “Main idea. Three supporting sentences. Conclusion,” he said. I hadn’t missed anything.

That evening, we wrote our first drafts. The man up front was an English teacher from a local high school. He had more charts to show us defining fiction versus nonfiction, the meaning of a story arc, and the many types of stories we could tell. “For this project, we’ll write fiction. The question is, should your story be a comedy or a tragedy? A fairytale or a mystery?” We took a break at 6 pm, which felt immensely grown up. I was too shy to talk to anyone, but I sized them up in my mind. Most of them were older than me and came from many schools, but none from my little elementary school on the far side of town. Some of the older girls wore tinted lip gloss. Which ones were the best writers? It was too soon to tell.

Back in our seats, we filled in Xeroxed story outlines with the genre we’d picked, our characters’ names, and our stories’ central conflict. At the back, I could see who was working and who didn’t know what to write. I filled in my worksheet and began drawing in the margins as others continued their contemplation. I added curlicues to the typeface on my paper and extended the answer lines into flowering vines, decorating the edges of my outline. The girls with the lip gloss elbowed each other and whispered, scribbling and erasing. At 6:30, we moved on to the writing, following our outlines to draft our stories. As I set to work, I reflected that in a two-hour session, half an hour of writing time wasn’t enough.

Mom was waiting for me in the lobby at seven, though I was the last to come out. As the others filed through the door, they gave me quizzical looks, which I ignored as I continued to work on my draft. The boys were the first ones out, followed by the lip gloss girls and the rest, all jostling behind me to get their coats. Finally, the lady in the sweater vest approached me. I kept my head down. “Five more minutes,” I said.

”I’m afraid not. There’ll be time to keep working in the morning.” I set my jaw for an argument, but her stern face was kind enough to discourage me. I saw Mom smiling through the glass door and knew it was time.

As we left, she held my hand on the way to the car, which I insisted on because it reassured me in a disorienting world. As we drove home, I told her everything, but most especially how I was the best writer in the room. Nobody else got what the teacher was saying. I was the first one to finish my outline and the only one determined to write until the last minute, until the clock ran out. Those girls with the lip gloss were all going to end up writing the same story because they only had one idea among them. Mom stopped me, reminding me that pride was a sin. I insisted it wasn’t pride. Why couldn’t I say that I was the best when I was?

”You don’t know that,” she said. “You didn’t see what the other kids wrote.”

”I saw how they didn’t know what to do, how they wasted time and asked each other for answers.”

”You shouldn’t spy on people. It isn’t nice.”

”I don’t spy. I just see what I see.”

”Why am I having this conversation with a ten-year-old?”

It was a question I heard a lot over the years. Why am I arguing with an eight-year-old? Why am I explaining myself to a six-year-old? Why am I defending my decisions to a four-year-old? When I heard it, I piped down, admitting I was wrong to think better of myself than others and promising to keep focused on my own work. I apologized and Mom accepted my apology. Then she surprised me.

”I know you’re the best in the class, Jennie. But you can’t hold that over people. And there may be a time when you’re the one who has something to learn.”

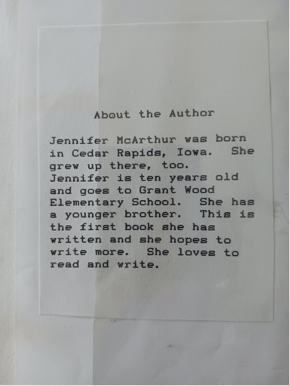

The Saturday and Sunday sessions went by in a whirl, the weekend unfolding through brainstorming activities, revisions, and the production of final drafts. I ignored Mom’s instructions about keeping my eyes on my own papers. As the hours passed, the worst students struggled to finish anything while I’d already had my revisions approved and sent off to the typist, a volunteer school secretary. She sat in the next room, taking just minutes to complete our grade school manuscripts. Meanwhile, I worked on my cover and title pages. My book was called The Mystery at 2316 Langley Boulevard. In it, a girl named Nicole and her faithful friends, Karen and Lissa, nab the thief who made off with her mother’s heirloom ring. It owed much to the Nancy Drew novels I read obsessively, incorporating a hint of Nate the Great, a grade school detective solving crimes around his neighborhood. With ten pages front and back, there were a lot of illustrations to do, pushing me to work faster than I wanted. Some drawings were less than my best, and the final courtroom scene was rushed, practically unfinished. But I had it completed for the last step when those of us who were ready (none of the lip gloss girls) glued our completed pages onto heavy paper before sewing the binding with needles and thin white string. With the addition of a little cardboard and a clear plastic book cover to finish it off, my book was done.

I rushed into Mom’s arms when she came for the parents’ hour. I showed her my work area, my pens and pencils, and the mismatched markers I’d used for the drawings. She beamed at everything, but most especially at me. When I showed her my finished book, she listened to me read every page with long pauses to soak in the pictures. When I asked if she wanted to read it again for herself, she did. The teachers came up to Mom one by one, each telling her how well I’d done, and I swelled with pride, soaking up their praise like a dry sponge.

At home, I showed Dad my work, and even he agreed I’d done an excellent job. He heard me read it once, glancing up at the illustrations. “I guess it wasn’t an art class,” he said, as he pointed out the flaws in scale and irregularities between pages. But he couldn’t squelch my sense of accomplishment at that moment. Mom told him sharply to keep his negative comments to himself, and, for once, he did. It was late, and I was tired after a long weekend. Mom kissed me goodnight as I lay reading a novel under the bedside lamp. “Don’t stay up too late. It’s Monday morning tomorrow.” She was right, and my eyes were already drooping, but when I put the book down, it called me back and wouldn’t even let me turn off the light. The inevitable chaotic morning was a lifetime away, and the stories were right here. I read and read, falling asleep with the light on. I opened my eyes momentarily when Mom came in to take the book from my slack hands. Then I drifted into my dreams where every girl makes her family proud, and every prince rescues his lady fair.

Leave a comment