Inspired by “An Area of Darkness,” by V.S. Naipaul

Since I was a little girl, I wondered about Oma’s country of origin. A country whose map I traced with wide eyes in my Deutsche Grammatik 1 textbook –a paper map on paperback—not a real country –and with my tiny index finger traced, I don’t remember how many times, its borders and would travel around the map until I found Hamburg and the river Elbe, from where Oma departed on a ship towards the North Sea, crossed the Atlantic, the Panamá Canal, called on the port of Guayaquil, Ecuador, and arrived to her final destination, the port of Callao, Perú.

Elbe River, Hamburg

Callao

Oma nurtured my imagination about her country of origin in many rich ways. Deutschland –I always used the German word for the country since that is how it lived in my imagination. Not “Germany.” Not “Alemania.” – “Deutschland” –Oma’s Heimat, a country not too much physically described by her unless I asked. One afternoon—I must have been 5 or 6–I asked Oma: “Are the trees in the Black Forest black? I knew “schwartz” meant black and “Wald,” forest.” She replied: “Nein.” “The trees are so lush that they form a huge canopy where sunlight would not go through, hence the name “Schwartzwald.” This image added more enticement to that place of my imagination.

It was Oma’s daily presence that brought me close to that imagined land. However, “Deutschland” was more of a concept, an “idea” created in my mind of this far away beautiful land full of impenetrable dark forests. Trying to understand the German language cases – Nominativ, Akkusativ, Dativ, und Genitiv— and adjective declensions–adjective endings depending on the “role” of the noun or pronoun in a sentence (like direct object or indirect object) – was as abstract and incongruous as the concept of “Deutschland”— of my childhood imagination. My area of imagination was this Deutschland in my own house in Lima, Perú, where Oma would teach me the language and speak to me in German when we were alone. Unbeknownst to the 6-year-old kleine Monika, Oma was transferring by reading folk tales, children’s stories and teaching the language, the concept of Heimat and Heimatlos that I would experience when I, too, left my homeland.

Deutschland –that area of the imagination was becoming a bit more concrete but at the same time abstract because, what is language if not emotions poured into air that the wind takes away. Oma was quiet, reserved, and melancholy. Her husband, my Peruvian grandfather, prohibited her to teach German to their children. Teaching me the language was our special bond. Trying to make this link to Oma’s Heimat more palpable, in my imagination I started “knitting” chain stitches using a crochet and with each little link, I was trying to create a long, long chain–one end starting in Lima, Perú, and the other, that would end in Hamburg, Germany. Knitting was a serious task for any 7-year old. I was thus creating a more serious imaginary land – the Antipodes to my real and concrete Peruvian homeland of playfulness and fun, where I walked, and ran, and swam in Cantolao Beach, La Punta, Callao, and played, and danced, and ate, and laughed with my loud cousins.

This more serious imaginary land was as abstract and impenetrable as the German grammar I tried to comprehend. Every time I asked Oma a grammar question, like for example, ¨Why does one have to write the masculine article “der” with a feminine noun in the Dativ?” (the Dativ designates the indirect object pronoun in a sentence), she would reply: “Because that is how German is.” I saw the rigidity of the grammar rules transferred to her rigidity and my mother’s rigidity, discipline, planning and organization that was also “transferred” to me via genetics or environment? Nature or nurture? In my imagination, I created my own Heimat or homeland of lush forests and pristine lakes and perfect houses with thatched roofs, white facades with wood beams and red geraniums, perfect red geraniums pots and bushes organized in rows like soldiers—everything in its place, in order, precise, “perfect” just like Oma and my mother are. “Perfect” as I perceived them as a child.

Oma’s appearance was impeccable. She dressed elegantly with blouses and skirts she sewed herself. Oma wore gloves in Winter. No señora Limeña would. She was tall, poised, elegant, and very polite. She had short shiny white hair and sky-blue eyes, so blue, like the summer sky, so blue that I would get lost in the immensity and depth of her stare when I looked at her with my little brown eyes. She spoke Spanish calmy, slowly and clearly with a heavy accent. What was intriguing, and to some Peruvians—comical–was how she would get the articles and nouns’ genders mixed up – the way I still do when I speak and write in German. She would say “el luna”-Der Mond or “la sol”-Die Sonne. Der is masculine, die is feminine. You see, in Spanish, “la” luna is feminine and “el sol” is masculine. Oma was always at odds with the Spanish language and with the culture—the extroverted fun-loving Peruvian culture.

She avoided birthday parties and tea parties. Oma only had three German friends, Ulla, Maria, and Hertha, and one Peruvian friend, la señora Pastor. Oma would take me along to visit one friend at a time. She never took me to tea parties like the ones my Peruvian great-grandmother, Carmen, attended where there were always eight or ten ladies all dressed in black. The widows’ black dresses, black shoes with little heels and black stockings were a stark contrast to the white table linens, white teacups, my pink dress, and the chatty and jovial ambiance. My great-grandmother was he antithesis of Oma: extroverted, sociable, fun, restless. I felt I was living two childhoods—the exuberant one with my Peruvian great-grandmother Carmen and grandmother Hermilia, and a more solemn one with my German grandmother, Auguste. People would think “la señora Augusta” was aloof. I just thought it was Oma’s personality. Later, as an adult, when I first moved to California, and I felt what she felt–that loneliness and sense of not belonging–I realized that she never fit. She was always a foreigner in Lima. She created her own “Deutschland” and very few were allowed in it.

Nunca se sintió en casa en Perú. Perú was never her home. She never drank tap water. She boiled and drank it at room temperature. She never ate ceviche. She never gossiped with neighbors. Even though she learned Spanish, she preferred to read in German. I loved our long walks to downtown Lima every other month to buy books at la Librería Alemana oblivious to the buzz and bruhaha of people walking in hordes and street vendors. It seemed like we were going to a piece of Germany in Lima. Oma was an avid reader. Every afternoon, after lunch, she would retire to her bedroom and read. She could not be disturbed.

Another piece of Germany was her bedroom. That was the only room in our house that we needed permission to enter. Puppe was strictly prohibited to enter. One severe stare at her and Puppe knew she had to turn away. Puppe was our German Shepherd. Puppe would sleep on my bed, roamed freely, and entered every room of the house—except Oma’s. Every time a letter arrived from Germany—that letter the bird brought in his beak, as the song says–, Oma’s eyes would swell with joy and anticipation. She would walk to her bedroom holding the envelope to her chest as if Germany was contained in that envelope, close the door, and stay there for hours. My brothers and I knew she needed privacy and would wait until that door that guarded Oma’s privacy like a medieval castle gate…… opened. I noticed how letters from Germany made Oma ecstatic, but I would really understand what she felt when I moved to California and received letters from her, my relatives, and friends from Perú. Hard to imagine that 20 years later one would receive Happiness just with a click of a mouse.

I, too, left my homeland. My parents did not want me to move to California when I was 23. Oma did not say a word about my decision. It was after Oma died, and I was living in California, that my mother told me Oma had left Germany because she fell in love with a man who was engaged to somebody else, so she decided to put an ocean between them-literally! Oma and I lost our homelands in dos malas jugadas del destino—two twists of fate. Then, and only then, I understood her melancholy. Melancholy that I, too, carry for the lost homeland, Perú. Oma never returned to Germany. She did not want to return to Germany– “vieja, pobre y fracasada” – “old, poor, and defeated.” Her marriage was a failure. Her health was poorer than her wallet. Oma was raised in a home where discipline and obedience was paramount. She lived a comfortable life in Germany. She would play the piano and read for hours. Her pastimes were horseback riding and ice skating. Probably, she disobeyed her father by moving overseas. I will never know. But I know she was a woman of integrity. And very proud.

As for me, after a failed romance in California, I also felt poor and defeated. Though young, I did not want to return to Perú. I went to Germany. Besides feeding my childhood with tales of a magical land of dark forests, animals who spoke German, white houses with geraniums, and strict grammar rules, Oma and I shared the same experience: The loss of the motherland. What intended to be just a song to fancy a child’s imagination, turned out to be a song of mourning.

CAPSULE 60 YEARS LATER

Hamburg, Germany

View of Hamburg skyline—that last thing Oma saw when she departed. An emotional boat ride for me.

The flight SFO-NY-Frankfurt-Hamburg I took 60 years after that ship departed from Hamburg, crossed the Atlantic Ocean, the Panamá Canal, touched on Guayaquil-Ecuador, and arrived in El Callao, Perú…. felt like the little bit of Oma in me was returning home. Frankfurt Airport was immense and modern as I pictured it in my head; however, Hamburg Airport was small and quaint. I descended the airplane using a ladder! Tante (Aunt) Elsbeth picked me up in her Opel. Not only did she welcome me, but all the Mercedes Benz in Hamburg! They were everywhere—not just cars, all the buses and trucks were MB. Blond and brown hair white people drove Mercedes Benz and Opels. Der Autobahn, superfast, as I had imagined. In my head I said “Willkommen!”

It was so different from Perú, where one would spot a Mercedes only in rich neighborhoods, and the buses and trucks were old, dirty and emit cumulus clouds of carbon monoxide. It was different from California, where one would see all car makes and models and people of different ethnicities and races driving them. The Germans I interacted with were solemn but polite. They use the formal you “Sie” like the Spanish “Usted.” When I arrived at Elsbeth’s house in Kellinghusen, a 25-minute drive from Hamburg, my cousin Maren, then 18, shook my hand in a businesslike manner. Accustomed to hug in California and kiss cheeks in Peru, I restrained myself and shook her hand too. Later, I observed that when she answered the home phone, she would say her last name, not “hello,” not “This is Maren.” I noticed what could be considered an aloofness—aloofness Peruvians back home perceived when they interacted with Oma. Yes! I had finally arrived in the mythical land of my childhood. A land “studied” in books, seen through family photographs, and spoon-fed by Oma.

“Hast du gut geschlafen, Monika?“ – “Have you slept well?” were Elsbeth’s first words the next morning. “Danke. Sehr gut!” – Very well, thank you! – I replied. I slept very well indeed. I had fallen sleep tired but happy. I was finally in Oma’s Heimat, my second homeland. I felt at right at home. This area of my imagination the “Deutschland” of my childhood was becoming a palpable reality. I slept in Kristian’s bedroom, a small bedroom in the attic with little windows, a small bed and a bookcase that covered one wall. The bookcase was full of books in German, English, Latin, and Spanish. Kristian was studying in Spain. I spoke to him in Spanish on the phone the next day! I had already met Onkel Hermann, a very polite, tall, blond man, Elsbeth, a short, sweet, and congenial lady, and Kristian, a curious and spirited 14-year-old, when they visited Yosemite two years earlier. Hermann was Oma’s nephew. He is Margaret’s son. Margaret was Oma’s older sister’s whom I had met only in pictures. Elsbeth showed me Margaret’s room. It was still intact. Nobody slept in that room. The next day, I met Oma’s youngest sister, Hanna. She was short, like me, had a round face, like me. She smiled at me and told me: “You have the same color of hair as Gusti and her same face. You are a Hamke.” I felt I belonged.

Tante Hanna – Oma’s sister.

We spent the afternoon together strolling downtown Hamburg and eating strawberry ice cream at a Kaffeehaus overlooking a serene lake that reflected the City Hall medieval structure, crowned by a patina-copper tile roof. My broken German, and Tante Hanna’s broken English seemed like vignettes adorning the shine in our eyes and the smiles on our faces. I finally finished knitting that yarn chain link and left my crochet on that Kaffehaus table a May afternoon under a blue Hamburg sky.

The next day, Elsbeth and I visited Auguste’s, Hanna’s, and Margaret’s childhood home. We walked for an hour or so until we arrived in a quiet street and there it was–just exactly as the picture I saw when I was a child. A two-story, plain cream-colored house with six windows and a door in the middle. The cloudy afternoon sky lent a sepia tint as the old photo. We looked at the nondescript house from across the street. “We are not going to knock on the door” Elsbeth said. “Your Oma’s stepmother still lives there.” I knew that after Oma’s mother died, her father married the neighbor’s daughter –two years older than Oma. Oma was 16 then. “You are right” I replied. (I did my mental math and figured– if Oma is 91, the stepmom would be 93 or 94). “It would not be appropriate to bother her.” I exclaimed. “Do you want to go to the Cemetery to meet your great-grandmother?” Elsbeth asked shyly. “I would love to.” I replied, as we walked down the elm tree covered street leaving the sepia house in the sepia background sky and back again to its photograph state in my childhood trunk of memories.

The cemetery was quiet and solemn, like Oma, like Northern Germany. Elsbeth led me to the resting place of my great-grandmother. The grey tombstone read: “Johanna Falk.” Time stopped in 1917. The year she left this world. I felt I went back in time to meet her “in person” and it was there and then that I understood the meaning of the song Oma would sing to me.

“Kommt ein Vogel geflogen…” was Oma’s:

mourning for the loss of her young mother

mourning for the lost love

mourning for the lost homeland

The melancholy Oma wore on her sleeve, the feeling of inadequacy or powerlessness, for not visiting her mother’s grave again, for not seeing the love of her life again, for not seeing the beloved homeland ever again was heavier than that tombstone and deeper than the Atlantic Ocean she traversed.

The area of my childhood imagination cracked open like a grave pit. This longing to visit Germany, so yearned for, since I was a child, crystalized, but I realized the Deutschland of my childhood was different from the soil I was standing on. The world that existed in the imagination of the child, which was the background of my childhood was an illusion not the real country I visited. What was real was the time I spent with Oma as a child and adolescent in Perú, learning German, reading folk tales and children’s stories, singing, and walking –just the two of us– the streets and parks of Lima oblivion to the buzz of people speaking Spanish loudly. I felt die Seele Deutschlands –the soul of Germany with Oma more than when I walked the streets she walked as a child. Oma war Deutschland. Omawas Germany.

The heavy Melancholy that I feel when I remember that song, or when I sit on the deck of my home and hear a vesper bird sing his sadness as the orange California sun sets, brings to mind the image of Oma in her Winter years sitting by the window in our Lima home—con la mirada perdida—with that blank stare- mirando un pajarito volar, looking at a bird flying –bringing to her a letter from her mother in her beak and sending back a greeting with a kiss, and saying she cannot reunite with her “weil ich hier bleiben muss-because I must stay here”—

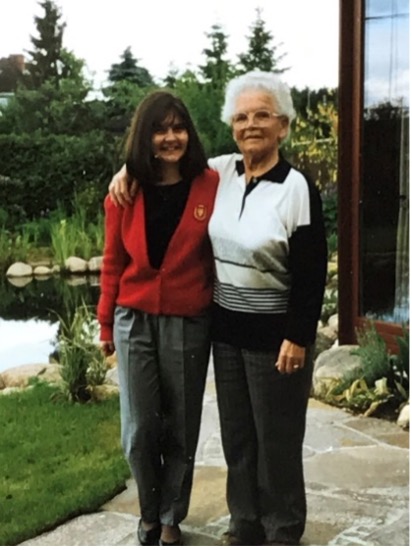

Visiting Oma in Lima after the trip to Germany.

Leave a comment